“I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent, but they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were when they got up and boy does that help, particularly when you have a long run ahead of you.” – Charlie Munger RIP, legendary American Investor.

Before we begin – this is the last shoutout for the Propenomix Advent Calendar – if you listen on a podcast platform, it is worth checking out the Propenomix YouTube for the daily posts I did throughout advent in December to celebrate getting to 500 subscribers on the channel! Thanks to all the regular readers and listeners who have subscribed……if you haven’t yet, what are you waiting for!? Please can you recommend me to a friend who you think would be interested? I love the commentary, feedback and interaction that I get on the channel, and am still at the stage where I can reply to every single comment. At the end today I’ll tell you a little about my content plans for 2024!

Welcome to the final Supplement for 2023. The one after the one after the antepenultimate Supplement – the ultimate supplement, if you prefer (yes, I know it doesn’t work like that). 1 more sleep until 2024.

So – very limited macro content this week. The Nationwide house price index was revealed for December, and the year – and the consensus was spot on, for the monthly at least. A 0% print to round out the year. The consensus annual movement was -1.4% and it ended up, according to Nationwide, at -1.8% (the consensus expectation for the ONS 2023 print is more like -2.5%, apparently, but we won’t know for a couple of months).

Other than that, we had truncated trading – just 2.5 days worth, rather than 5 – in the bond and stock markets – because of the time of year. You know a lot more about the bond markets because of this year’s efforts in the Supplement I’m sure – I’m not sure how many join me in checking on a regular basis, but I certainly see a lot more people referring to the 5-year SONIA swaps than I ever did before, that’s for sure! I’m pleased to have helped the cat out of the bag on that one.

The 5-year UK gilt opened the week at 3.306, and closed at 3.313 – with nothing really to change it, that shouldn’t be much of a surprise – although it is worth looking at the range too. The lowest trade was a shade under 3.25%, and the highest a little over 3.4% – so there was twice as much amplitude to the upside as the downside. However – I wouldn’t read too much into this as volumes are very light on a week like this. The 5-year SONIA swap closed the week at 3.347% yield – and it feels great to end the trading year looking back at a print of 4.035% just one month ago and 4.021% a whole year ago.

Those 65 basis points are just gigantic, and whilst the trend needs to continue and the pressure in the economic media is ramping up on the Bank of England, the reality is that other than the RINO potential recession already referred to last week, there is no real significant economic problem in the immediate pipe before the election, and the economy is likely to rebound in Q1 2024 which will take some of that pressure off if the more hawkish members of the committee continue to believe we need to hold hard in rates. I’ve said it before – I think the 50/50 market on a rate cut in March offers value on the “hold” side, just from analysing the previous MPC voting patterns over the past couple of years.

The lackro of macro leaves us a nice hole to get into one final deep dive of the year, and the timing is great for this week – the Bank of England have just published a nice juicy report in their Quarterly bulletin entitled: “The buy-to-let sector and financial stability”. That definitely sounds like the type of thing we should be interested in – remember, these findings are hat-tips to potential regulatory changes (such as the 125% ICR rules and 145% rules that were brought into play in 2017). I’m sure you’ll join me in agreeing that they are well worth being in front of, not behind.

I cast my mind back to when Mark Carney was the Governator of the BoE, and he often spoke about the property market, landlords, and buy-to-let. Mr C’s impression – which was really educated guesswork, rather than data-based, was that landlords were the riskiest part of the housing market. More likely to sell assets in a fast downturn, and offering more volatility. Of course, we would most likely have to agree with him. It is unlikely that homeowners would sell faster or more aggressively (or at more of a discount) in the face of a downturn – buy-to-let landlords also face more expensive mortgages, with less tolerance on arrears, and less consumer protection. Of course we, as landlords, are strong custodians of our assets – but the argument would be that the one we care about the very most would be our own family home. Probably fair.

So – Carney obsessed over controlling the market in the event of a repeat of a 2008-style event, or other future credit crunch or event of significance. It certainly was more of a topic in the quarterly breakfast briefings that I’ve attended for many years when MC was the top dog vs Bailey. We’ve hardly spoken of property at all since Bailey took the reigns.

You might consider that a bonus, really – one fewer person or organisation that has landlords in its sights. However – what would we really want from an intelligent Bank of England? One that recognises that the PRS is an essential part of the housing mix in the UK, and one keen not to shock or drive many out of the marketplace with monetary policy – being aware of the broader impact that might have on the financial stability of the UK – which is, remember, a secondary brief to the bank (whereas the primary stated goal is to get inflation to the government-set target – and since that’s not going well and hasn’t been for a couple of years, I guess we should expect more chat around the rest of the Bank’s raison d’etre).

This paper actually also follows up on a paper that the Bank published on 12th September, which was part of the Bank’s “Bank Overground” series of publications, which is intended to summarise a piece of analysis that supported a policy or operational decision.

I haven’t line-by-lined it – the analysis is too graphically based, and too long, for that to be a useful exercise for either of us. Instead I’ve opted to summarise both of these pieces of work in one, so that we can, together, start to understand more about exactly where the Bank is at on buy-to-let as we come into 2024.

The strapline on the September report is not catchy, but gives you a clue as to where the Bank are at on recent claims around the buy-to-let sector and the overall landlord hostility that has prevailed since George Obsorne’s “genius” policy decision to introduce a “special” tax for landlords by amending section 24 of the Finance act back in 2015, reducing tax relief on mortgage interest to single out “landlording” from basically all other businesses in the UK when it comes to debt – but only when considering properties owned in people’s personal names.

The September paper asks the question – “Has the private rental sector been shrinking?” – and underneath, it points out that “An innovative measure of landlord property transactions shows the UK private rental sector has likely been shrinking for at least the last two years, but less quickly than other indicators suggest.” It feels to me that the authors of the paper were coming from a place where they did not believe as many landlords were leaving the sector as was being claimed – but let’s get into the detail and find out just how objective – or not – they are.

They open by recognising the reduction in profitability for landlords. At this point it is a good idea to point out a distinction that the Bank prefers to make – they are defining a buy-to-let landlord as one who owns one or more properties that they rent out, with mortgages. That last bit is key, because it is often forgotten. If you own a property (or more), unencumbered, you are not a buy-to-let landlord in the Bank’s eyes. You are just a landlord, or part of the rest of the PRS. They don’t really have an exclusive name for it. It’s implied that you are very wealthy – although it might be one property worth 30k in the far-north-east of England, or one property that you lived in 30 years ago and retained when you moved house back then – so you wouldn’t necessarily be rolling in it in either situation, at all.

They also recognise the problem with measuring the size of the sector. This has been a problem for as long as I can remember, and I agree with it. However, we do have enough large organisations with enough data to have a pretty good go at this – the issue is really twofold. One – as an organisation, how can the Bank make any decisions without the data being correct; and two – politically, you can always choose the “better” or “worse” looking dataset to make a political point and be technically “telling the truth”. Not ideal.

Being unhappy with the data, they are doing their own thing as a bit of a mash-up. Understandable, and here’s the criteria they are using:

Matching the land reg with Zoopla-WhenFresh data on rental advertisements (WF is one of the largest data aggregators out there, used by many big banks to make decisions) in order to work out which properties were bought with the objective of renting them out, and when properties that were rented out were then sold and NOT rented out to count the other way.

These then drop into 3 categories:

- Landlord to owner-occupier sales

- Owner-occupier to landlord sales

- Landlord to Landlord sales

It’s an interesting metric, which is likely better than what’s out there – because what’s out there is really disappointingly poor. It also strikes me as sizeably flawed, for the following reasons:

- They use a 4-year time window between when a property is rented and sold, or bought and rented/not, to determine their graph. This isn’t even the average length of tenancy in the UK

- It’s only England and Wales – with different rules, you might be best off leaving out Scottish data, but it is a lot to leave out

- The data tracks FCA/UK Finance data on buy-to-let mortgages (until 2020) almost perfectly, then departs from this line significantly. It isn’t clear why.

It all looks a bit of a mess, because UK Finance data is only tracking new buy-to-let mortgages when a certain element of the sector only proceeds in cash for a number of reasons which we all know. This isn’t really explained, but I am really not convinced on this “new measure” on which the Bank is giving us an explanation of.

The Bank’s new measure is basically showing smaller outflows than other measures (Hamptons produce survey data which is held to be a good proxy, but again I would have to disagree – Hamptons go no further north than Stratford-upon-Avon, and have a huge concentration in London and the South East – so their data just can’t be representative of the entire country). The Bank show much larger outflows as a percentage in London and the South East – and that’s what we would expect, of course, because the lack of gross yield (before we even start on costs) has been choking landlords in the South East ever since rates reverted to more “normal” levels over the past 18 months or so.

They know the data isn’t great, but their point would be that this measure is better than whatever else is out there – and perhaps it is, but the number of swiss-cheese-style holes I can see in it never fills one with confidence.

The “point” in the conclusion that they would have drawn is that the sector has “only” been shrinking since mid-2019, although the gap between the two lines has grown significantly since then as you can see. This isn’t congruent with other numbers that show the peak PRS at 2016-17, which makes more sense as that’s the time lag after policy took a restrictive, if not hostile, turn at the Bank’s level and the governmental level. Nonetheless, this is a report prepared by economists, not political scientists, and so there we go.

This report was presented to the Bank in Q2 of 2023 – and the very recent report is a product of that analysis as well. This one goes into much more detail, which the committee no doubt asked for on the back of the previous report.

Firstly – why does the Bank really care? Because they want to measure or estimate just how much risk to financial stability the buy-to-let sector might pose, based on interest rate changes. They don’t care about the politics of renting – and immediately seek to put all this into context when they frame the market – some of this data you’ve already seen or heard in the Supplement this year, but it is worth repeating:

- 19% of households are privately renting, and of them, 45% live in a property with a mortgage

- BTL is therefore about 9% of the housing stock, using the Bank’s definition of the BTL sector

- The size of the BTL sector is £300bn of mortgage debt or 18% of the overall outstanding mortgages in the UK in systemically important banks

- 35% of households own outright and 30% own with a mortgage. These figures are slightly different to others that have been seen this year, but only by 1-2% or so

- That leaves 17% of households who are social renters (actually, there’s some rounding somewhere because those 4 percentages add up to 101%)

We mostly know our history I believe, and this is a reminder of the fact that BTL is such a young sector still. 1988 and the Housing Act made renting much more viable than it had been before, but BTL as defined here was really born in 1996 with the advent of the Buy-To-Let mortgage. In 2007, it is recorded as having been 25-40% cheaper to rent a home than to service a mortgage, because house prices had gotten so very high compared to wage development. The data – as always – says it best. Between 2000 and 2008 the BTL mortgages outstanding went from £9bn to £140bn (a 1556% increase, yes that’s no typo)

Between 2008 and 2015 this loan book still grew around 8.5% per year – since 2015, it has been more like 5% per year (but still grown – hence the move to £300bn in the most recent figures the Bank is using).

How does the Bank perceive the danger posed by BTL? In two ways – firstly, the resilience of the lenders if landlords cannot service mortgage debt – either direct defaults on those secured loans, or defaults on other loans that landlords have that come down when the whole house of cards collapses. Secondly, the Bank is also concerned about the borrowers – which here really counts the landlords and their tenants – they may have to cut spending sharply or sell houses, depending on which side of the fence they are sitting – but the Bank is interested in both scenarios.

The Bank recognises that there can be a compound effect here, and that one of these problems may impact the other – something that got missed far too often in the run-up to the financial crisis.

The next part is particularly interesting – the Bank’s viewpoint on their toolbox to manage risks stemming from BTL:

- Loan to value policies, limiting loan to values based on the FPC’s powers of direction (the Financial Policy Committee, who would instruct the PRA – the Prudential Regulation Authority – to change these if they deemed it necessary having done more research).

- Affordability policies – firstly the PRA affordability test, which was extended to Buy-to-Let in 2017 – Taking into account rental income, the borrower’s income, essential personal expenditure and living costs, income tax liabilities, professional fees incurred through the ownership, the cost of voids, council tax, the cost of utilities and the management of the asset the borrower is borrowing against

- The second affordability policy already in place is around what we talk about as ICRs – interest coverage ratios – i.e. 125% of the mortgage needs to be the market rent to get a 75% mortgage on a 5-year fixed, otherwise the test is 145% of the mortgage, usually keeping LTVs lower, which particularly bites in lower yield areas and led to fewer 2-year mortgages being viable, particularly in the South-East

- The remainder are Capital policies which I have not discussed extensively thus far – the technicals may well be more than any of us need to understand in too much detail – but they involve the stress-testing framework (for the annual stress test that the Bank undertakes on the entire Banking system, not just BTL) – The Countercyclical Capital buffer rate – and also Sectoral Capital Requirements.

The final three are much more macro and somewhat abstract, and so I’m not going any further into those at this point. They are much more lender-focused rather than decisions about individual assets, classes and whether a property is “suitable” for a buy-to-let mortgage.

Now into some more detail – since September 2016 any PRA-regulated lenders have been required to apply either or both of these guidelines:

- Income affordability testing at a stressed interest rate of at least the higher of 5.5% or a 2 percentage point increase in BTL mortgage rates. This test is used when lenders are taking account of a borrower’s personal income as a means to meet mortgage payments, which is defined as top slicing

- Interest rate affordability stress testing (ICR testing) to ensure that rental income is sufficient to pay interest costs, after accounting for maintenance and other costs of letting. Lenders tend to test affordability at a minimum ICR of 125%, assuming stressed interest rates as above, and the basic rate of income tax. For higher and additional-rate taxpayers, the equivalent ‘breakeven’ ICR is about 167%. In practice, lenders have tended to test those borrowers to 145%.

If the political idealogues who detest the fact that there exists a buy-to-let sector wanted to have a reasoned argument, it is the second of these bullet points that they would disagree with. It should be self-evident these days that 125% (i.e. 80% of rent can be used to pay the mortgage) is simply not enough coverage. Compliance costs have skyrocketed since this directive. Maintenance costs have increased over 100% since 2016, well above the level of either inflation or rent inflation. Insurance has taken a steep shift upwards as well.

That’s before you apply section 24, where of course as a higher rate taxpayer (or a “false” higher rate/additional rate taxpayer, forced into the band by your revenue rather than your profit) you cannot expense all of your mortgage interest costs. 125% becomes a complete joke then – although 145% is a bigger joke.

Still – the recent wobble in the market, thanks to rates rising so much and so quickly, has not flushed this weakness out of the system. Lloyds – the largest bank in the UK – tends to prefer a 160%+ cover ratio for all of its loans, and that strikes me as a much more realistic approach.

It isn’t ALL bad. I would hate a portfolio at 125% coverage, but if it was fixed rates for 25 years, I’d be looking forward to the annual rent increase significantly as the cost of debt would be staying static and be being inflated away by the capital growth and inflation as well. That’s an extreme example, but just to give a little of the other side of the argument here.

It’s also worth quoting this directly from the report (before my knickers get too twisted):

“These testing requirements do not cover all BTL lending. They exclude lending with a fixed-rate period of five years or more and lending by non-banks, which together comprised about 75% of BTL new lending in 2023 Q3. However, banks also apply their own affordability testing standards outside of the SS 13/16 requirements”

It would be good to know the split between what was 5+ year fixed by choice, 5+ year fixed by necessity (because the stress tests on lending shorter than 5 years simply priced these loans out for the vast majority of borrowers), and was by a non-bank (a non-bank is an organisation that is not an officially established bank, but offers many similar services).

There was also a footnote to this comment in the report which was of significant interest at certain points over the past 18 months:

“The requirements also exclude lending to corporates, consent-to-let loans, lending prudentially regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), loans with a term of 12 months or less, and remortgaging with no additional borrowing.”

You might start to wonder what they DO actually include. Assuming corporates means any limited company, this also excludes all bridges and all remortgages where capital is not raised (which will have been a lot, given the price of the debt at some points during 2023!).

As covered above, it is reasonable to expect BTL landlords (as defined) to sell more quickly than homeowners in the event of a credit crunch or other event of financial distress and significance. The data here that the Bank rely on is what happened in 2008 – where BTL mortgages in 3+ months of arrears increased 6-fold compared to owner-occupiers in 3+ months of arrears – they “only” doubled.

Indeed – those whose BTL mortgages originated in the 90-95% band were 3 times as likely to default as homeowners in the same origination band. That in itself justifies lenders charging a higher rate for BTL than to a residential owner-occupier – the risk of default trebles in difficult times.

There is recognition that underwriting standards pre-08 were also rather weak (some would say tracing paper, or “pulse optional”, for those who remember some of the loans that were being written back then). I also found the next paragraph particularly interesting, and again am going to replicate it in its entirety:

“During the Covid downturn, however, the BTL market was significantly more resilient. In particular, arrears increased only marginally over 2020 before recovering to record lows. Arrears have picked up since the start of the current monetary policy tightening cycle, but the increase has been contained so far. Much of this can be explained by improved underwriting standards, which support borrower and lender resilience. The next section covers these standards and their effects.”

Let’s see. I’d suggest that perhaps arrears also stayed low because of the significant direct-intervention bailout style action that took place quickly, compared to the complete lack of action that took place in 2008, when instead it was 6 months even before base rate was slashed. Inflation in wages and benefits has also helped to keep pace with rental inflation, and also the prevalence of fixed rates above variable rates when compared to 2008 is significant.

The next section shows – I think – why the Bank is not as worried as I am over ICRs, but I would suggest I’m trying to be proactive rather than reactive. I’m going to borrow another paragraph from the report:

“The median ICR at origination stood at almost 300% in 2022, up from 242% in 2015. Following sharp increases in interest rates since end-2021, the ICR distribution on new lending has shifted significantly lower, reflecting pressures on the market. But we expect ICRs to recover somewhat going forward, as there is evidence that landlords are passing on costs to renters. And many landlords have significant ICR buffers. For example, 83% of new BTL mortgages taken out in 2022 had an ICR greater than 200%, well above ‘breakeven’ levels.”

I’m not sure the 2022 ICR stat is particularly helpful. WIth an average of 4-5 months to get a loan over the line, loans completed in 2022 were more often than not at the “old money” rates of 3-4%. This doesn’t speak to mortgages taken out in 2023 which are much more likely (in BTL) to have been at the 5-6% level – and 6% is double 3%, at the extreme. My point really is that I think this could easily be understating the problem, and one of the issues here is of course the lag in the data. 2023 has been so incredible in terms of the volatility in rates – really very unusual – that what happened last year may as well be 3-4 years ago.

The text doesn’t really match the image they use in the report. All of the improvement between 2015 and 2022 was wiped out and completely inverted by Q3 2023 – and it is a great example of the stress that’s been put on the sector in the interim/of late. I would have used this as this week’s image but there’s one even better and more informative one that I’ve opted for.

12% of BTL stock at the end of 2016 had an LTV of 75% or more. By 2023 Q2 this was down to 6%. I’d expect this to have increased a shade since then, but if many have not re-geared or released capital, then perhaps not – I’m thinking of the number of loans with 3-10% arrangement fees added on top in order to get the pay rates down, to get under the ICR rules.

This will, probably, all be fine with the pace at which rents are increasing – as I refer to above, if year one at 125% looks pretty glum, year 4-5 should look pretty good if the assets are managed adequately and competently.

The next bit really surprised me, and shows you that we can often all be guilty of living in our own little bubbles: The seven largest UK lenders (Lloyds, Barclays, Nationwide, Santander, HSBC, Virgin and Natwest) extend the majority of BTL loans, responsible for around half of new lending. Specialist lenders and smaller banks add another 22%, building societies account for 15%, while non-bank lending accounts for 13%.

I can’t believe more than half is the “big 7”. Mortgage works is owned by Nationwide, and they are the biggest, of course – but more than half stuns me. Just shows you!

The next part is an admission of what we have all known is happening, and is of course driven more by George Osborne in 2015 than anything else:

“Historically, BTL landlords have operated on a small scale, but the sector has been consolidating…”

BTL has passed its peak as far as Joe Public is concerned. More recently, margins on new purchases have been crushed by the meteoric increase in interest rates. In any business, when margins get squeezed and sectors stop growing, there is inevitable consolidation. This is just no surprise at all, but it is good to see it being recognised here.

The next part of analysis rests on the 2021 English Private Landlord Survey. I’m not going to spend a lot of time on it – the data for the survey recipients (9000) was grabbed in January 2021, nearly 3 years ago now. Central Bankers are never in a hurry but this is so slow and the changes to the sector have been so great in magnitude, I just don’t see this as worthwhile. I’m not blaming the Bank or the report writers here – this is just how bad the data is. As an aside, the ONS are overhauling how they report rental data as they know their methodology is flawed – they are working on it, and it is better than nothing, but they are still an “official statistic in development” as they now call it.

I thought it was then worth replicating the next table in the report in its entirety. Imagine my excitement at a new acronym for Section 24, too:

| Higher ongoing operating costs for BTL landlords |

● Interest rate increases from 2021 onwards. ● MITR removal, phased in from 2016–20. The removal of MITR increased the ICR required for additional and higher-rate taxpaying BTL landlords to ‘breakeven’ on their mortgage expenses. |

| Regulatory changes |

● Changes to Stamp Duty Land Tax (from 2015) imposed an additional 3% transaction cost on properties sold to be rented. ● Capital gains exemption reduction (from 2022) makes it more expensive for landlords to sell properties. ● Basel 3.1 Risk Weightings (2025) may increase lenders’ costs of financing BTL mortgages, particularly for high LTV mortgages (of which there are few). ● Forthcoming Renters (Reform) Bill will aim to abolish fixed-term assured tenancies and impose new obligations on landlords in relation to rented homes. |

So – s24 to a Central Banker is rather known as MITR. Worth searching for that acronym to see how often it comes up – I know the NRLA, Ben Beadle and many other s24 campaigners will be pleased to see it mentioned in a report by the central bank – for the good it will do. At least it is recognised as one of the main issues at hand.

Likewise, the Renters’ Reform Bill (RRB) is recognised as something heaping further pressure on the sector by an apolitical organisation. By the way – if this is the first time the Basel 3.1 Risk Weightings (2025) has appeared on your radar – welcome to the club! It’s not finalised yet (and is on the desk of the PRA, the Prudential Regulation Authority that form part of the Bank) but when it is, suffice to say it will be being taken apart in the Supplement.

The problem with a table like this, of course, is that it is just a list. There are no weights here. Many would argue, correctly I believe, that sections 24 and 21 respectively of the finance and housing acts, and their application or removal, are far bigger news for the sector than the 3% additional SDLT weighting (not recognised in the report of course, but 4% in Wales and 6% in Scotland, remember). CGT allowance reductions is frankly a pebble in the pond compared to “the Sections”. The punchiest of all, though, one might argue, is that little line at the top – “Interest rate increases from 2021 onwards”. Never mind the quality, feel the width.

There’s also recognition that higher returns are now available on lower-risk assets. Yes, its party time compared to 3 months ago in the bond markets for us borrowers, but still orders of magnitude above where we were at: high 2s for a 5-year fix, to us praying for low 5s (with a comparable arrangement fee to the high 2s days).

There then follows some stats I’ve been after for a LONG time, and they put some real colour around conversations around affordability that are simply bandied around by some commentators in the industry with no real evidence behind them. As you can tell, I’m delighted (remember, I am the geekiest of data geeks, in case you didn’t already know!).

I MUST make this caveat clear here though – and this is where data can be misleading. For this to be meaningful in the big wide world beyond the Supplement and my love of analysis, you’d also have to know the average AGE of a renter versus a mortgagor. I’d expect mortgagors to be older – but just how much older I don’t know – and here I am, also making those assumptions. But we’d need age to look at a proper cross-sectional analysis or make comments around social mobility – the idealogues wouldn’t wait for that before passing judgement on this next part!

“At £26,500, the median renter’s gross income is less than half that of the median mortgagor (£59,000). About a quarter of renters report spending more than 37% of their gross income on rent (Chart 7). Among private renters, the median income is around £35,200, and the mean housing costs as a share of income is 28%. Renters also tend to have much lower savings to draw on than other households. Nearly 28% of renters reported having no savings in the NMG 2023 H2 survey, and about 50% reported having less than three months’ worth of rent in savings.”

28% is there as the average, including London. Affordability ex-London is measured at 33.3% as a ceiling by most agents. The long-term average (not listed here) is around 27% – which shows you just how much “incredible pressure” is on renters at the moment. It is largely bluster, as evidenced in my works on this subject in July this year (9th July Supplement in case you missed it). The savings side is no surprise, although this is not compared to the average social renter vs the average private renter, or the average mortgagor, of course. The analysis is also somewhat biased to show renting as being worse than it is – because the comparators are cost of mortgage vs cost of rent, whereas you’d be better using something like the ICR or similar to gross up the costs of owning a home versus the costs of renting one (Insurance, compliance, maintenance, agents arguably, etc.)

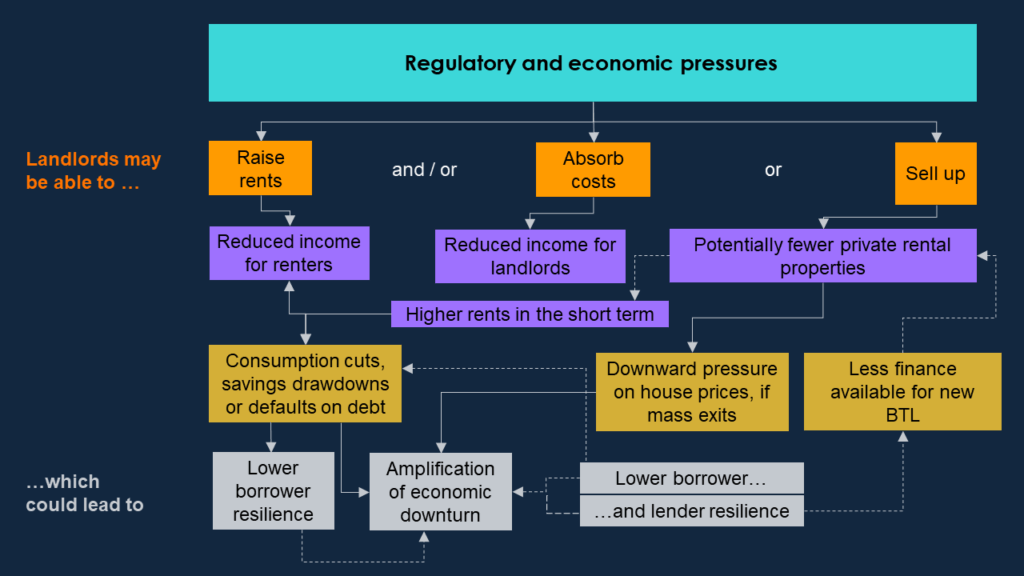

Now follows this week’s image. I really liked this one, and it was very hard to select only one from this report – but there’s no doubt this was the one to choose. It is looking at what landlords may do – and how that might affect lender and borrower resilience, amongst both landlords and renters. Some might argue this leads to the least biased type of analysis that you will see in the sector! It is only as good as the data quality of course, but still – likely a vast improvement over much of what you see in the media or from the big organisations who see forecasts as more of a marketing exercise than anything else.

For those listening – these are the (basic) options that the Bank is considering here:

Landlords might be able to – Raise rents, and/or absorb costs, or sell up

Raising rents means lower income for tenants. Absorb costs means lower income for landlords. Selling up means potentially fewer properties in the PRS, which would lead to higher rents in the short term.

Raised rents (either way, from fewer properties or raised rents to cover costs – or both) would lead to consumption cuts, savings drawdowns or defaults on debt from renters. Fewer BTL properties, in case of a mass exit, could also put downward pressure on house prices. This could lead to lower borrower resilience, amplification of an economic downturn, and lower borrower and lender resilience (and the consumption cuts, savings drawdowns or debt defaults, plus lower lender resilience could also feed into the economic downturn).

One more point – lower lender resilience could lead to less finance available for BTL, which could lead to even fewer BTL properties.

This is supposed to be “could dos” and theoretical scenarios – but I think this is pretty realistic for a downside case. I hope this report gets in front of the right Governmental operatives in this, and the next, administration!

The worst case conclusions are then put into some context, which makes sense. LTV ratios are lower than the GFC, and arrears have not jumped up too quickly (although they have been trending upwards, and the data lags a fair amount of course). The non-bank lenders are identified as the biggest risk – since so much of the sector is still funded by the “big 7”. This part certainly makes me think – a much smaller percentage of my debt is “big 7” across my own group, and my own pie chart would look significantly different with much more exposure to non-bank lenders. Something to consider for all of us who are regular customers of secondary lenders.

The 3-month BTL arrears rate was 0.6% in Q3 of 2023 – so relatively current – and the 3-month owner occupier rate was 0.9% up from 0.8% in the quarter before – so BTL is still sitting relatively securely although the Bank does omit to say just how much those have increased since the past couple of years (but, with lots of “easy money” around, of course arrears were even lower!).

A bit more in specifics directly from the report around non-bank lenders that is worth reading in its entirety:

“But some non-bank lenders could be vulnerable to funding risks in the residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) market. Around 9% of the BTL stock of loans is securitised, compared with around 5% for owner-occupiers. The RMBS market is sensitive to changes in economic and market conditions, and in investor appetite. As such, tighter financial conditions could restrict access to funding and/or drive-up funding costs for some lenders, especially those relying on securitisation.”

It might be pleasing to note just how LITTLE of the market is being securitised still with the scars of 2008 still being visible to many, of course. Having said that – of course – securitisation in itself was not the problem, incorrect risk pricing was the problem!

The Bank currently sees the decline in the size of the PRS as “moderate”. That is probably fair. It isn’t the size in absolute numbers that matters of course, however – the point made well by Richard Donnell in the recent Zoopla report was that when you have 1.3 million people enter the UK in 2 years, the vast majority will rent, so even with the same number of rental homes (or a growth) that’s a gigantic amount of pressure being put on the sector.

The next part looks like a fair assumption – although it does assume that people would not break mortgages/pay ERCs. I have challenged this fixed mindset aggressively over the past couple of years, as long term readers and listeners will know! Nonetheless, here is what the Bank thinks which doesn’t look dramatically incorrect:

“Nevertheless, the high share of five-year fixed-rate BTL mortgages reduces the risk of a significant share of BTL properties being sold at once, because the impact of higher interest rates is staggered. The share of five-year fixed lending has increased significantly since 2014, likely reflecting mortgagors seeking to lock in low interest rates. In addition, long lead times for regulatory changes give landlords time to adapt to the changing economics of the PRS.”

Fine – but this only lasts until the most recent 5-year mortgage drops off, for loans completed before end 2022 let’s say. I’d want to be monitoring just how many properties were sitting on variable rates waiting for the market to improve a bit before shifting them – as I think it’s reasonable to posit that there might be a couple of hundred thousand such properties out there by the middle of next year, unless rates really are going to crash back down.

It’s also fine having “time to adapt” but referring back to the image, if there’s only raise rents and/or absorb costs, or sell up – I don’t see alternative options being considered (and, indeed, this analysis is incomplete because as I’ve referred to many times this year, more active asset management strategies are to be considered – short term rentals, HMO, social housing, etc.) – so this effect is being completely ignored. How “active” are BTL landlords, really, though – I’d suggest not that active, although you rarely know whether people are unencumbered or not!

The Bank has a model which goes through a stress-test scenario of 30% of landlords selling up, which only sees a 4% adjustment downwards in the house price in the longer run (shorter-term volatility could well be larger of course). The Bank also, of course, understands that s24 only affects 45% of landlords (ignoring corporates) as 55% are unencumbered.

The Bank has generally here missed the nuance that interest is not the only fruit, however. It would be nice to see some robustness in the analysis here (I appreciate they might consider it to be outside the scope but……) – in percentage terms, what is maintenance inflation? What is compliance inflation? What is insurance inflation? Compared to rent inflation and also the increase in mortgage costs – mortgages are a major cost, but if you follow their logic and numbers of a 300% ICR, that means mortgages were 1/3rd of rent and if you are using agents, then in this environment you are likely not far off 1/3rd of rent in those costs too – i.e. the other costs of being a landlord are as high (or were as high, before interest rate increases) as the mortgage costs. What I’m saying there (in a roundabout way) is that anyone with an ICR under 150% is losing money – that’s a bit bearish, but is a better yardstick than 125% as a breakeven in my view!

For the next paragraph, I’d love to get some feedback here. Here are the Bank’s pronouncements:

“The gross rental yield on BTL investments has averaged around 6% since 2014. But net rental yields (which account for property running costs and mortgage costs) have decreased significantly since mid-2022. For an average BTL property, the net rental yield was around 3.5% in Q2 2022. Since then, higher mortgage rates imply an average increase of around £2,500 in annual interest payments for BTL landlords. Full pass-through implies a net rental yield of 2.5%.”

I get this. This is accurate for a relatively mature marketplace, of course. BTL has been going since 1996 as discussed, and pre-2008 there were a lot of properties purchased with those legacy mortgages still out there (indeed, the very largest omission in this report is just how many are on pre-2008 trackers, I have seen estimates of this data at around half of the properties out there, but have my doubts as to its veracity. In the absence of a better measure, though, it’s the best we have got). We are all very pleased that the bond yields are moving downwards, when thinking about new stock – because that’s the relevant rate – whereas those million loans on trackers are dependent on the base rate, which I’m still maintaining isn’t going to fall as fast as everyone thinks (I expect at least 2 very frustrating MPC meetings next year, if not more).

More useful would be the case for new stock, I’d have thought – because some discussion around the replacement rate (or whatever you want to call it) is needed to even attempt to model this accurately.

This is the detail that the Bank provide around their pronouncements above:

“The value of an average BTL property is around £260,000, the gross yield is around 6%, and annual operating costs, including taxes, are £2,350”

I’m not here – average rent £1,300 on a 260k property – that sounds believable – but average costs 15% of rents including taxes? In what world, sorry? I’d really love to know where this comes from because I just don’t see it being accurate. Sadly, the report writers don’t reference this point.

The next part looks very fair though, and I have replicated it without adding anything:

“Rather than absorb costs, landlords could seek to raise rents further. There is a risk that landlords cut consumption, run down savings, or default on other obligations, in order to service their BTL mortgage – but we judge this to be unlikely. In the first instance, landlords are likely to try to pass some costs on to renters. UK private rents increased by 6.1% in the 12 months to October 2023, the largest annual change since the series began in 2016. Rents on new lets increased significantly more – by 10.5% in the UK in the year to September 2023, according to Zoopla. And around 13% of renting households reported experiencing rent increases above 20% in the 12 months to September, according to the NMG 2023 H2 survey. In the near term, higher rents are likely, given rising mortgage costs and strong demand.”

10% of renters in 2020 reported being in arrears at some point in the past 12 months. That number is now 14%, so the pressure of rising rents is telling.

The Bank then find a very clever and erudite way (too long to replicate in its entirety) to say that they aren’t really concerned about tenants in terms of the financial stability risks they pose because a) they don’t tend to have secured loans – not much to secure against being the argument and b) renters can’t cut consumption as much as others can because there’s less to cut. Indeed, this next stat would upset a few because of its brutality, and you can argue over what is titled “non-essentials” – but it really is food for thought:

“On average, private renters spend £246 per week on non-essentials, compared to £177 for social renters and £384 for owners. By simple calculations, renters account for about 23% of non-essential expenditure (14% by private, 9% by social renters), and slightly more than 30% of overall expenditure (20% by private, 12% by social).”

So – we are 75% of the way through the report. Well done for staying with it – I found it absolutely fascinating reading just because I do really value what the Bank of England thinks about our sector. In many ways it is one of the most important articles I’ve read this year – the New Year’s Eve timing might not be perfect (or it might be – other things are generally quiet at this time of year, let’s face it).

Next they try to address a question that many have been positing but all have struggled to really evidence – Is the private rental sector shrinking? (I think we know the answer is yes, and the real questions should be – how quickly? And also – will it turn around, and when?)

The Bank has the same frustration as I do, and many others do. There are no available measures that actually capture the size of the PRS. The Bank’s summary of the current measures:

- Homes listed for sale within three years of being advertised for rent (Paragon).

- Implied changes in the BtL mortgage stock (UK Finance).

- Number of second homes subject to capital gains tax (HMRC).

- Real estate agents’ own record of the share of properties bought and sold by investors, applied to HMRC property transactions to estimate whole market numbers (Hamptons). This is the only external estimate to include a net balance, rather than focusing solely on outflows”

Hamptons’ data is not bad at all and their predictions have not been outrageous in recent times, compared to some of the others who should be hanging their heads in shame as they totally misjudged inflation and the price of housing in a tough 2023.

We saw the Bank’s conclusion earlier on – that the sector has been shrinking since mid-2019 in size, although they are keen to point out in several ways that that shrinkage is overstated by the measures listed above. I think that’s reasonable – but they miss out one gigantic point which we could divide into two.

Net migration. Since mid-2019, around 1.9 million more people have entered the UK. As already referred to in the Zoopla report analysed last week, 90%+ of this number are likely to rent. A static PRS (let alone a falling one) represents a change in 2 million people (in household numbers of 1.25 as renters, on average – or 1.6 million more rental homes needed than in 2019.

This hasn’t happened of course, and there just is not that much void stock. So how has it worked – well, in reality, several hundred thousand have come from Ukraine and taken up residence in people’s houses to start with. HMOs have been created (net), I’m sure, which will have picked up some of the slack. Voids are halved according to some of the semi-reliable data out there. And – of course – many are housed in temporary accommodation, hotels, or in other alternative ways. Of all the ideological positions I hear taken on this subject, the one I never hear taken is that a functioning PRS could pick up this slack – which, of course, it could.

Even if there WAS appetite for that, though – and some of the more liberal voices in the debate in 2023 have started to understand that controls are NOT the way forwards, and started to understand that given the scale of the PRS and lack of alternatives, that working with the sector would be the smartest and best thing to do for the tenant – it would take quite literally years to undo the damage already done and reverse this trend.

Anyway – we are at the end of the longest Supplement of the year, aside from the Bank’s conclusions – this sentence may at least tickle the heart a little:

“The BTL sector has grown significantly over the past two decades and has become an important and integrated part of the UK financial system.”

The Bank recognises the large change in comparative returns – BTL margins crushed whereas other safer assets (bonds) are right back in the mixer for many (and associated retail products, such as building society or challenger bank fixed rate products).

Pressures are out there, but the sector has been robust. There’s a significant amount of patting themselves on the back for the ICR rules and the rest of the framework – as I discussed, personally I think it is somewhat weak, but there you go. It is better than it was, and I’m always cynical when anyone is marking their own homework.

They conclude that even if there was a large exodus, prices wouldn’t suffer much but rents would rocket. Put this alongside Hamptons’ recent claim that rents will rise 4 times as much as house prices (as a percentage) over the next few years, in a report I will save for a future supplement!

The savagery of the conclusion which could be reframed as “renters don’t have that much money and therefore anything they do is unlikely to be a big deal” isn’t personal – it’s just a refresher of how brutal a discipline that economics is. They’ve done the same exercise for mortgagors just this year and concluded “they can handle it” (and they have been right) – so it’s just the turn of renters to be discarded at the macro level.

The best result for the tenant would be that some of the more lunatic “foaming at the mouth” rental reformers read this report and make up their own mind. If any of them do read this, I’m very happy to debate them on a platform of their choosing (not number 9 at Kings Cross, in case they push me off, although they’d have to be quite strong to do that) – feel free to share this near-thesis with anyone you think would like to get involved in that!

The very biggest well done for getting to the end – one final nudge for the Propenomix Advent Calendar – (There are 48 videos in the series, 24 60-second explainers and 24 longer-form explainers – all under 10 minutes). Subscribers are very, very welcome, and here are the links – for the channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpNyNRdTJF87K3rUXEV3s-Q and here to the Propenomix website: https://propenomix.com/ – thanks for supporting me spreading the word, more subscribers will lead to more and better content. For the last time in 2023 – Keep Calm and Carry On!

Adam Lawrence